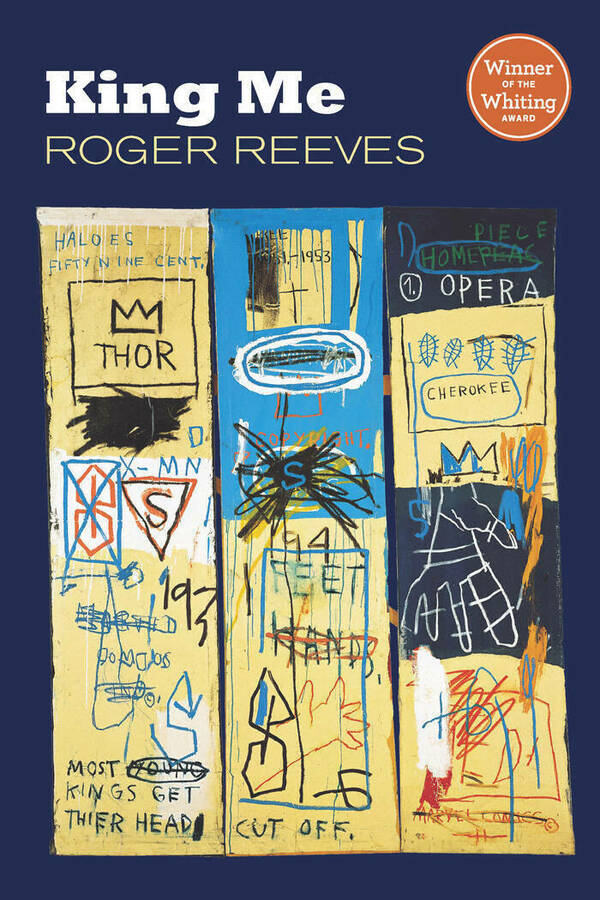

Arman Chowdhury: The cover art for your debut poetry collection, King Me, is an artwork by Jean-Michel Basquiat called Charles the First, which in turn is a tribute to jazz musician Charlie Parker. Both Basquiat and Parker make appearances in your poems in King Me. On the bottom-left corner of the Basquiat cover art, there’s a line that says, “MOST YOUNG KINGS GET THEIR HEAD CUT OFF.” In the poem "Some Young Kings," you rewrite this line as, “Most young kings return home without their heads.” I wonder if you could talk about the urge to engage other artists and art forms in your work. How would you situate your art in relation to Basquiat’s and Parker’s, for instance?

Roger Reeves: Art, seems to me, is always a conversation with what has come before it. As artists, we are nothing but an aggregation of our influences, our loves, our desires, our hates, our experiences. Artists like Charlie Parker and Jean-Michel Basquiat, in their making, provide material for my own making. Basquiat’s paintings, and Parker’s runs and solos are not to be treated as museum pieces, but are to be taken down from the walls, taken out of the recordings, examined, revised, played with.

Parker and Basquiat also stand at an interstitial space for me, the interstitial line between mastery and the deformation of mastery, eloquence and the deformation of eloquence. In Parker, there’s his innovation in terms of bebop, extending the jazz tradition (a type of deformation), but there’s also his practice. Parker is famously known for getting his butt handed to him at cutting contests as a young man. Rather than think he had no facility with his horn, he holed up in his house and practiced. He revised himself into genius. I think about this sort of revision, play, and practice as useful for me—it doesn’t have to come out like Mozart—in one take—but I can revise into genius. Basquiat’s cross-outs perform a similar sort of lesson. In the quote above, you visually re-present Basquiat striking through a word he painted. This sort of revision is beyond “style” or “swag” or “flair” but is a way of thinking about error, revision, and play. In this way, he moves against eloquence and simultaneously makes an elegant phrase. Quite simply, both Basquiat and Parker “say” what they need to say in whatever color, tone, timbre, or register. It’s a Malcolm X school of poetics—by any means necessary.

I can revise into genius.

AC: King Me is filled with keen observations of the non-human world. You invite a lot of birds, animals, insects, and parasites to inhabit your poems, living or dead. You let the creatures exist on their own terms, exist next to humans but not in service of. Why is it important to include non-human living beings in your poems? How do they (productively) complicate your observations and arguments regarding the human world?

RR: It is important to include non-human living beings in my work because non-human living beings exist, express sentience, and inflect upon the “human,” and we, “humans,” inflect upon non-human living beings. I can’t help but think of the opening of scholar and poet Fred Moten’s In The Break: “The history of blackness is a testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.” In this case, “objects” refers to Black folks. And, it’s Moten’s troubling of the “human” and playing in that abjection that contributes to my deployment and thinking about non-human living beings. I want to trouble sentience and our hierarchizing and aggrandizing the human. I’m also interested in thinking about how inadequate the notion of the human and humanity is in its relationship to subjects like human rights, philosophy, and the history of racial capitalism. In fact, the human and humanity might be the actual problem—what we think it means and what it allows us to do to those that are not considered human. My thinking is quite influenced by writers and scholars like Sylvia Wynter, Cedric Robinson, Ruth Gilmore, and Bruno LaTour.

AC: In his novel Erasure, author Percival Everett exposes biases in the publishing industry, rooted in racial assumptions, that essentially dictate who gets to produce what kind of literature. The protagonist in this autofictional novel is a Black writer whose work often gets rejected by editors and is confusing to reviewers when the subject matter of his books has no bearing on his race. In the book, one reviewer writes, “The novel is finely crafted, with fully developed characters, rich language and subtle play with the plot, but one is lost to understand what this reworking of Aeschylus’ The Persians has to do with the African American experience.” The protagonist’s frustration lies with the fact that white writers aren’t subjected to the same standards. Would you say Black writers, or writers of color, are more scrupulously scrutinized regarding what they (ought to) write about? Given that your own work generously engages various cultures and histories, what is your opinion on what is and isn’t off-limits for an artist in terms of subject matter? And how does “authenticity” figure in this debate? Are we less authentic as artists if we write about people or issues that are apparently far removed from us?

RR: Yes, Black writers or writers of color are more scrupulously scrutinized regarding what others feel they should write. This statement is not new or ground-breaking. It’s a water is wet sort of statement. However, I think it is a truth that bears repeating, bears remembering and saying—much in the way that there will be more books written about the Civil War and George Washington every year. Unfortunately, the literary critical tradition of commenting, assessing Black creative work begins in racism with Phillis Wheatley’s preface written by the twenty-one White gentlemen of Boston in 1773 authorizing and authenticating that indeed Wheatley wrote the poems in the book herself, and with Thomas Jefferson’s dismissal of Wheatley as a poet in Notes on the State of Virginia because ‘religion could make a Phillis Wheatley but it could not make her a poet.’ Did she/he/they write that thing that they said they wrote and is what she/he/they wrote really a poem, novel, short story, etc. are the two historically racist entry points or poles of literary criticism that focused writings by Black folks. Check William Dean Howells’ review of Paul Laurence Dunbar. However, scholars and poets like Meta DuEwa Jones, Brent Hayes Edwards, Evie Shockley, Randi Gill-Sadler are asking different questions: questions about how Black writers do what they do. These scholar-artists start from the place that Black writers have a presiding intelligence that is historically and aesthetically rigorous.

But you’ve asked me about writers and writing and what is off-limits. I think nothing is off-limits to the writer. But, whatever one does choose to write about, do it well, thoughtfully, ethically, compellingly. Be nuanced. Be large, gracious, complicated especially when depicting others. I will never tell a writer what they can and cannot write. However, at the end of the day, we must deal with what’s on the page and whether that succeeds.

Fascism is en vogue in the United States (not that fascism wasn’t here before (i.e. America); it's just that it felt like before Trump, fascism was the uncle who slept in the basement and only came out every now and then to buy some Black and Milds. Over the last five years, it feels as if our feckless uncle became the school board president, mayor, chief of police, and the ombudsman at the local college as well as the dogcatcher).

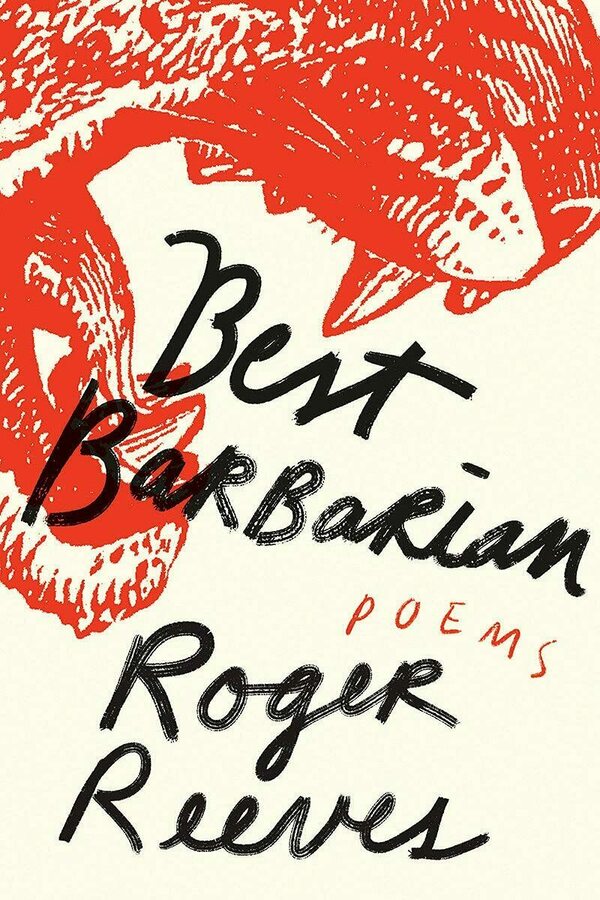

AC: The New Yorker published two of your poems within the last year and a quarter: "Grendel" in September 2020, and "Standing in the Atlantic" in October 2021. Are these poems part of your upcoming collection, Best Barbarian, out in March 2022? There are textural similarities between these poems and the poems in King Me, but the newer poems seem to have tighter focus and quieter language. The language almost approaches a narrative form in the newer poems, appearing more vital in its conviction, more total in its devastation. My reading might be far from accurate as I don’t have access to the entire collection, but I wonder what you have to say about Best Barbarian in your own words. What are you grappling with in the new collection? Where does it converge with King Me? Where does it diverge? Has your view of the world changed between the publications of the two books?

RR: The two poems you’ve read in The New Yorker are from Best Barbarian. I think the language is quieter as you noticed. And my obsessions are my obsessions—how to live as a Black man in a country that is hostile to my living, aesthetics, beauty. Yes, all of those concerns were in King Me. However, in this new collection, elegy is more front and center because of the passing of my father and me passing into fatherhood. When my daughter was born, one of my earliest thoughts was, “I’m going to die.” Something about her birth signaled my death in a visceral and totalizing fashion. My death became real to me in a way that it was not before. Hence the quietness. I think I passed into something there. And, in Best Barbarian, I’m trying to think about (not figure out) what it is that I am passing into—metaphysically, aesthetically, lyrically.

Also, the manuscript is written through the end of the Obama presidency into and through the Trump years. America was all ‘burn, baby, burn,’ and as my mother said, the tension in the air felt just like the 1960s. Fascism is en vogue in the United States (not that fascism wasn’t here before (i.e. America); it's just that it felt like before Trump, fascism was the uncle who slept in the basement and only came out every now and then to buy some Black and Milds. Over the last five years, it feels as if our feckless uncle became the school board president, mayor, chief of police, and the ombudsman at the local college as well as the dogcatcher). Also, overt racism could and can get you elected and help you gain Twitter followers. So you know, the world felt a little different, and that difference shaped my language, shaped the experience of language and shaped the book I wrote.

AC: Are you working on any projects at the moment, poetry or otherwise? What are you most excited or hopeful for regarding the future?

RR: I am currently working on a book of essays called Dark Days. We’re finalizing contracts now so I can’t quite announce it. I’m also working on a book of short stories and a novel, as well as writing new poems. Always writing new poems.

What am I most excited or hopeful for regarding the future? The revolution my ancestors have been and are continuing to fight for.

Roger Reeves’ poems have appeared in journals such as Poetry, Ploughshares, American Poetry Review, The Nation, Best American Poetry, and The New Yorker, among others. He was awarded a 2015 Whiting Award, two Pushcart Prizes, a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University, a 2013 NEA Fellowship, and a Ruth Lilly Fellowship by the Poetry Foundation in 2008. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin. His first book is King Me (Copper Canyon Press, 2013), which won the Larry Levis Reading Prize from Virginia Commonwealth University, the Zacharis Prize from Ploughshares, and the PEN/Oakland Josephine Miles Literary Award. His second book of poetry, Best Barbarian, is forthcoming from W.W. Norton in February of 2022.

Arman Chowdhury is an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at Notre Dame. He is a prose writer from Dhaka, Bangladesh, interested in studying and writing fiction that challenge traditional modes of literary realism and that frustrate the desire for a stable and coherent world. He studied Creative Writing and Biomedical Engineering at Vanderbilt University. At Notre Dame, he is also an Environmental Humanities Initiative (EHUM) Fellow and a Graduate Affiliate for Literatures of Annihilation, Exile & Resistance. His work has been supported by The Loft Literary Center, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.