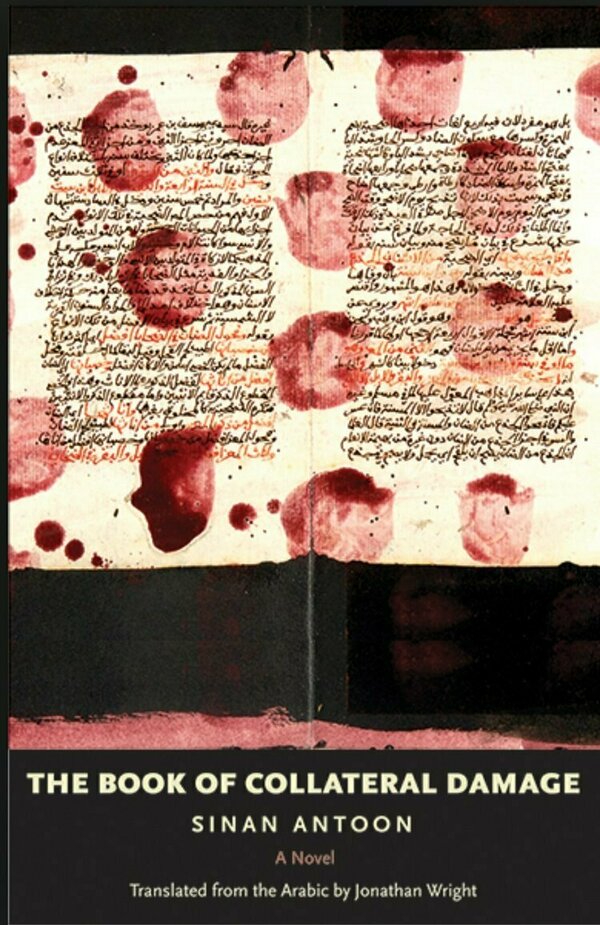

Sinan Antoon is a poet, novelist, scholar, and translator. He was born in Baghdad and left Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War. He holds degrees from Baghdad, Georgetown, and Harvard where he earned his doctorate in Arabic Literature in 2006. He has published two collections of poetry and four novels. His works have been translated into thirteen languages. His translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s last prose book In the Presence of Absence won the 2012 American Literary Translators’ Award. His translation of his own novel, The Corpse Washer, won the 2014 Saif Ghobash Prize for Literary Translation and was longlisted for the International Prize for Foreign Fiction. Two of his novels were shortlisted for the Arabic Booker. His scholarly works include The Poetics of the Obscene: Ibn al-Hajjaj and Sukhf (Palgrave, 2014) and articles on Mahmoud Darwish, Sargon Boulus, and Saadi Youssef. He returned to his native hometown in 2003 to co-direct About Baghdad, a documentary about Baghdad after dictatorship and under occupation. He has published op-eds in The Guardian, The New York Times, The Nation and various pan-Arab publications. His latest novel, The Book of Collateral Damage was published by Yale University Press in 2019. He is an Associate Professor of Arabic Literature at New York University and co-founder and the editor of the Arabic section of Jadaliyya.

This lyrical, philosophical, and deeply moving novel follows a young writer and academic, Nameer, from Baghdad to New England to New York. Antoon chronicles Nameer’s obsession with a mysterious Iraqi archivist named Wadood, who is attempting the impossible project of accounting for all that was lost in the first second of the American invasion of Iraq. In this novel Antoon interweaves Nameer’s narrative of exile with explorations of beauty, trauma, loss, and discovery, exemplifying Walter Benjamin’s exhortation: “He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging.”

I asked Sinan Antoon about the craft of writing and translating his hybrid and multi-genre novel, the current state of MENA literature in the U.S., and the function of beauty and humor in a narrative of loss.

Sara Judy: You play extensively with genre in The Book of Collateral Damage. In the final sentence of the text, your protagonist Nameer identifies the book as a novel. However, elsewhere in the text, Wadood’s project – which is contained in the novel – is described variously as a history, an archive, and a catalog, all descriptions which could be applied to your book. The novel also contains letters, notebook pages, and references to theoretical texts; there are moments of lyricism in your prose that read like poetry, as well as moments when Nameer sings snippets of song, translates poetry, and keeps newspaper clippings. Not to mention the moment at the end of the novel, when Nameer is Xeroxing information about the Arabic novelist Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq, who is credited with writing the first Arabic novel (described as an “innovation”). Is this a novel, as Nameer suggests, or is the generic category more blurred? How would you describe the genre of The Book of Collateral Damage?

Sinan Antoon: The boundaries of any genre are constantly shifting and moving. There are always texts that try to play with those boundaries. Texts defy, cross, or “violate” such borders, with various degrees (and effects) of playfulness and seriousness. I’ve always thought of the “novel” as the most open space with the greatest potential to invite and host other “genres” and discourses without limits. It’s quite tempting to explore the potential, but also risky, of course. The Book of Collateral Damage is in conversation with pre-modern Arabic and Persian books. Its original title in Arabic (Fihris) refers to al-Fihrist, the encyclopedic work of Ibn al-Nadim (10th century). I’ve been fond of pre-modern Arabo-Islamic prose classics and fascinated by the variety of genres one could find in a single book.

Wadood’s project may be described as an unfinishable encyclopedia of destruction.

Wadood’s project may be described as an unfinishable encyclopedia of destruction. Both he and Nameer are in search of the most appropriate form and genre to write about Iraq and its recent history. They write from different locations (Wadood is in Baghdad and Nameer is in New York) but are trying to collect shards and fragments of Iraq’s history and their own shattered personal histories. The book also tells its own history; how all these fragments are collected by Nameer. It is also about how a novel comes into being.

SJ: Throughout the book, Wadood consistently resists Nameer’s offers to publish or translate any portion of his catalog. Fihris (translated as The Book of Collateral Damage) has been in the world as a published work for almost four years, and in its translated form in English for almost a year. Has your relationship with the text changed over that time? Did you have any of Wadood’s reticence toward the publication and translation of this text?

SA: Wadood’s perfectionism, paranoia, distrust, and general despair, all make him reticent about publishing or translating excerpts from his work. Paul Valery wrote that “a poem is never finished, only abandoned.” I share Wadood’s reticence (for different reasons, mostly) but I eventually succumb and set the text free. I experience conflicting feelings whenever I’m working on a novel. I want to finish it, of course, but I find immense pleasure in residing in its world and being with my characters. Wadood’s manuscript could have included so many other objects. There was that temptation too. I know, from previous books, that I will go through post-partum depression once I’m done and will yearn for my characters, so I procrastinate and extend my stay as long as possible. With every novel there is a moment when I read it after it is published, not as its writer, but as a reader. I touch the book and smell it and realize that it has an existence that is entirely independent of me. I’d wanted to translate the novel myself, but didn’t have the time to do it, so I agreed to have it translated when the translator approached me.

SJ: Can you comment on the state of MENA literature in the U.S., and how you locate yourself in that literary landscape? You’ve written elsewhere about the way Islamophobia in the U.S. has a homogenizing and reductive effect that ignores difference among people from Arab countries. This symposium is organized under the themes of “annihilation, exile, and resistance,” and your work engages movingly and powerfully in that work of resistance—but I imagine it’s an exhausting position to have to maintain. I’m thinking of the translation fatigue Nameer describes at various points in the novel, especially when interacting with and explaining himself to his neighbors and colleagues in New York. I’m also conscious of my own subjectivity as a white American woman asking you these questions. Are there poets, novelists, or other writers you admire, or see yourself in conversation with, who help alleviate that fatigue?

SA: Three decades ago the late Edward Said published an essay entitled “Embargoed Literature” about the politics of translating and publishing Arabic literature. Much has changed since then and much hasn’t. Some of the structures and market dynamics that overdetermine the circulation and reception of cultural production from MENA are still there. 9/11, the ongoing War (of Terror) on Terror and its aftermath, and the rise of Islamophobia have intensified what I call “forensic interest” in Arabic (and adjacent) literature. Arabic literary works are oftentimes read as cliff notes for geopolitical events, or anthropological clues to some essence. This symposium is one of those rare sites that allow us to resist and problematize this reductive discursive violence.

Arabic literary works are oftentimes read as cliff notes for geopolitical events, or anthropological clues to some essence. This symposium is one of those rare sites that allow us to resist and problematize this reductive discursive violence.

I’m in an odd position. I often feel that I’m a stranger in the literary landscape in this country. I don’t teach creative writing and am not part of the MFA ecosystem and its networks. Because I write my literary works primarily in Arabic, I’m treated as a foreign writer in many ways. I don’t mind that, because, like Nameer in the novel, I don’t feel at home in the United States. I’m aware of the many privileges my location allows me. But, as I wrote elsewhere, I feel like a barbarian in Rome. My situation is not unique. Because of dictatorship, sanctions, and wars, a disproportionate number of Iraqi (Syrian and Palestinian, too) writers live in the vast diaspora.

Poetry is my prayer. Reading (and translating) Charles Simic is always an antidote. The poets I admire (and whose lines I recite almost on a daily basis) were also displaced and lived significant periods of their lives in the diaspora: Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008), Saadi Youssef (1934-), and Sargon Boulus (1944-2007). Boulus, in particular, is a favorite and frequent interlocuter, for many reasons. He left Iraq at a young age and lived most of his life in San Francisco. He was initially enamored with America and its promise, but his disillusionment grew gradually. The brutality of the 1991 Gulf War shocked him. Some of his late poems reflect on what it means to live in the belly of empire, in a country that is destroying his homeland (Iraq). I am working on an anthology of his poems, as well as a monograph on his poetics.

SJ: I want to end with a question about beauty, joy, and humor in this novel. As much as your work is invested in holding open attention to what is lost, and to the sorrow and unending grief of that loss, there’s also a delicate and finely tuned attention to beauty. The “Colloquy” passages are invested in looking closely and carefully at that which is delicate and ephemeral—feathers, film, postage stamps, the strings of an oud. War is an ugly thing, a violence which only makes rubble and death, but the novel tries to hold together the delicate pieces of these beautiful things for us to see. What role do you see for beauty in the work of resistance?

There is plenty of pain and destruction. But there is beauty, too, among the ruins. And this beauty is at times a solace, as well as a defense against destruction and brutality.

SA: We live in a violent world, shackled by the forces of predatory capitalism. There is plenty of pain and destruction. But there is beauty, too, among the ruins. And this beauty is at times a solace, as well as a defense against destruction and brutality.

The flood is an important theme in mesopotamian mythology, and in the poems of the aforementioned Boulus. The morning after the flood has uprooted and swept away so much, humans begin, once again, to reconstruct their lives. They pick up the shards and remains and rebuild homes, material and discursive. They mourn, re-member, tell stories of life, before and after the flood, and they sing, to survive. Poems, novels, and songs, are houses to shelter beauty.

Sinan Antoon is a poet, novelist, scholar, and translator. He was born in Baghdad and left Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War. He holds degrees from Baghdad, Georgetown, and Harvard where he earned his doctorate in Arabic Literature in 2006. He has published two collections of poetry and four novels. His works have been translated into thirteen languages. His translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s last prose book In The Presence of Absence won the 2012 American Literary Translators’ Award. His translation of his own novel, The Corpse Washer, won the 2014 Saif Ghobash Prize for Literary Translation and was longlisted for the International Prize for Foreign Fiction. Two of his novels were shortlisted for the Arabic Booker. His scholarly works include The Poetics of the Obscene: Ibn al-Hajjaj and Sukhf (Palgrave, 2014) and articles on Mahmoud Darwish, Sargon Boulus, and Saadi Youssef. He returned to his native hometown in 2003 to co-direct About Baghdad, a documentary about Baghdad after dictatorship and under occupation. He has published op-eds in The Guardian, The New York Times, The Nation and various pan-Arab publications. His latest novel, The Book of Collateral Damage was published by Yale University Press in 2019. He is an Associate Professor of Arabic Literature at New York University and co-founder and the editor of the Arabic section of Jadaliyya.

Sara Judy is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Notre Dame's English Department, and a Ph.D. fellow in the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study. She studies twentieth- and twenty-first-century American poetry and poetics, with a focus on religion and literature. Her dissertation examines the ways in which twentieth-century poets self-critically adopted prophetic rhetoric—to varying degrees of success—as a way of attempting to intervene in social and political issues of their time. Sara is an active volunteer with the Moreau College Initiative at Westville Penitentiary, and she has also served as managing editor for the journal Religion & Literature. Sara is a 2021 recipient of the Kaneb Center Outstanding Graduate Student Teacher Award, and her course was featured by the Ansari Institute for Global Engagement with Religion. A graduate of Notre Dame's Creative Writing MFA, Sara's poems and reviews have recently appeared or are forthcoming in The Adroit Journal, Ghost Proposal, EcoTheo Review, Psaltery & Lyre, and elsewhere.