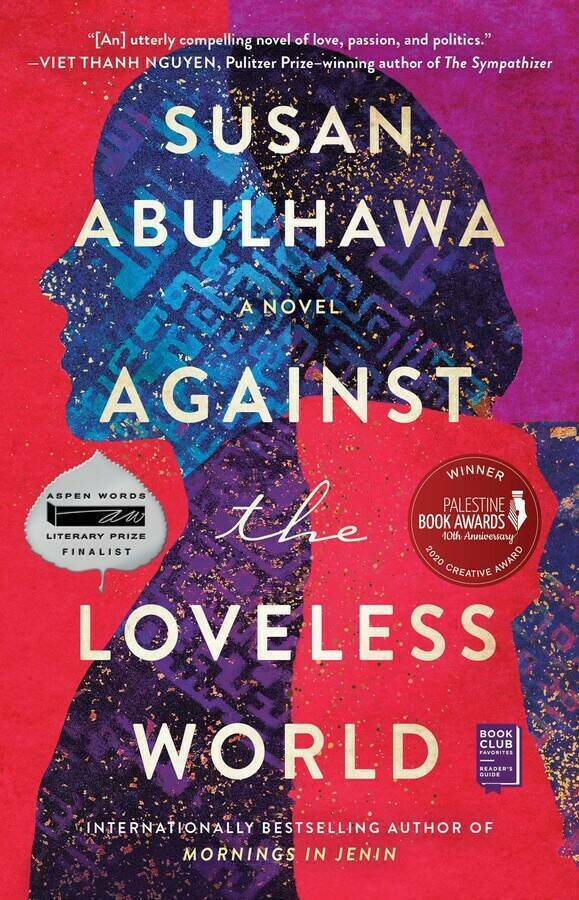

susan abulhawa’s most recent novel, Against the Loveless World, traces the path of a young Palestinian woman, Nahr, from Kuwait, to Jordan, to Palestine, to an Israeli isolation cell she calls “the Cube.” After being abandoned by her husband, Nahr meets an older woman, Um Buraq, who coerces her into working as escort for Kuwait’s rich and powerful men, until the U.S. invasion of Iraq forces Nahr’s already displaced family to flee Kuwait for Jordan. Nahr travels to Palestine to seek a divorce from her husband’s family and unexpectedly falls in love with Palestine—and with her ex- husband’s brother, Bilal. In Palestine, Nahr becomes more politically conscious and commits herself to clandestine resistance against encroaching Israeli settlements.

Narrated by the passionate, candid Nahr herself, this is an unapologetically political novel. In the face of exile, violence, and occupation, love—as a transformational force and radical act—nevertheless shines through. I spoke to Ms. Abulhawa about the complex women who make this novel so compelling, the many forms of violence shaping their lives, and how to situate the Palestinian struggle in its appropriate contexts.

Rachael Rosenberg: I first want to ask you about the protagonist of this novel, Nahr. I found her to be such an engaging heroine and narrator. Her personality was really refreshing—she can be blunt, she has strong opinions, she cracks vulgar jokes. Nahr has some rough edges, yet we also get to see her tender side in this beautiful love story you crafted between her and the character Bilal. Can you tell us a little bit about how she took shape as this multifaceted character and what it was like to tell the story of her turbulent life in her voice?

Susan Abulhawa: Nahr was probably my favorite character to write since I began writing novels. But the process of developing her character was very much like all the others. I had only a sketch outline of her life when I began writing. Her personality and spirit unfolded through the many iterations of the story, and in many ways, she is the one who dictated the nuances of her own character. Creating a fictional character involves getting to know them and listening to them in one’s imagination.

RR: There are so many forms of violence shaping the lives of the characters in this novel: the violence of displacement, exile, and imprisonment; the structural violence of unjust institutions; the destruction of homes, cultural practices, lifeways—the list goes on. The type of violence that I found most difficult to read about, however, was sexual violence. How did you approach writing scenes that included sexual violence, and did you wrestle with the implications of including them?

SA: The starting point for this novel, in fact, was the sexual violence. Sexual assault is something that the vast majority of women throughout the world have experienced (and/or will experience) to varying degrees. I’ve personally made no secret of the sexual violence I endured at various stages of my life, as I believe that public conversations about it is the only way to begin dismantling this particular form of violence. With this in mind,

I knew the subject of sexual violence was something I was going to write about, particularly as it relates to the sex industry in the Arab world, which is a big open secret. The main challenge for me, which would not have been a challenge if I were writing in Arabic rather than English, was ensuring that I was mindful of, and able to avoid, Orientalist traps and pitfalls.

RR: I also want to make sure to ask you about environmental violence, because the land itself is such an important presence in this novel, and through Nahr’s eyes, we fall in love with it. I was especially moved by the grove of trees, which are both a site of cultural meaning and a source of sustenance. Eventually, the trees also become a means for resistance against Israeli settlements. How does the relationship between the people and the land shape the experiences of Palestinians, both in Palestine and in diaspora?

SA: The natural world plays a big part in all my novels, as it does in my own life. Palestinian society, in particular the fellaheen, collectively have a reverence, curiosity, and respect for trees that I’ve rarely seen in other societies. Israel has always understood this, as do their paramilitary settlers, which is why tree groves have been particular targets for their violence against us.

RR: Um Buraq was a character I really struggled to come to terms with, yet at the same time, I appreciated how complex and morally gray she was. Um Buraq essentially blackmails Nahr into working for her as a sex worker, but she also takes her under her wing and tries to teach her the ways of the world, and she helps to get Nahr and her family out of Kuwait. She strikes me as one of Nahr’s most important relationships, perhaps even more important than Nahr’s relationship with her mother. Even after many years apart, at the end of the book, Um Buraq still understands Nahr on a profound level. What does this relationship tell us about both exploitation and friendship between women?

SA: Writing the relationship between Um Buraq and Nahr was as much a pleasure as it was a challenge. I think the reader rightly will dislike, even despise, Um Buraq in the beginning, just as Nahr does. But as their friendship unfolds and Um Buraq herself comes into greater focus, you can see a genuine affection and trust between them.

Um Buraq herself was a victim. She was also a feminist without ever knowing the word feminism. People are complicated and the relationships between exploited women take on many layers.

There’s nothing worse in literature than reading a novel with two-dimensional characters who are wholly good or wholly bad. It’s just not believable.

RR: One of the passages that I found really thought-provoking is when Nahr criticizes the conventional framing of the relationship between Israel and Palestine as a “conflict.” Her view is the framing of a conflict between two sides creates a false equivalency and obscures the real dynamics of the situation (I’m paraphrasing). Reading those pages, I felt that I had been called out. It reminded me that scholars and scholarly institutions are often either complicit in or actively uphold systems of oppression in many ways, including the acts of naming and defining. Within the field of peace studies, many scholars now are debating whether peace and peacebuilding as theory and practice can be decolonized and, if so, what that actually looks like. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on this—is it possible to divorce our understandings of peace, violence, and conflict from coloniality?

SA: It’s easy to fall prey to words of a discourse already engineered by others. For example, the term “peace in the Middle East” has become so common as to be cliché, but there’s a strategic reason it was never “justice in the Middle East.”

True peace is just a byproduct of justice, and that’s the word I prefer we use when describing our aims. Indeed, the colonization of Palestine is not a “conflict” any more than slavery was a conflict, or apartheid, or Jim Crow, or the annihilation of Indigenous Americans. That term cannot apply in circumstances of such extraordinary asymmetries of power.

A conflict is something that happens between equal powers who disagree on something. A settler-colonial movement, armed with the most advanced death machines, going about replacing and erasing a principally unarmed, defenseless indigenous population is not a conflict. It’s a lot of things—barbarism, colonialism, ethnoreligious supremacy, cruelty, criminality, immorality, thievery—but it’s not a conflict. There are so many other such terms, intentionally injected by Zionists into popular discourse, that people take for granted and repeat without weighing the meaning of it. It’s important for us to consider the words we use when we speak about Palestine.

RR: Towards the end of the book, we learn where the title comes from in quite a beautiful way. It’s a quote from the James Baldwin essay “A Letter to My Nephew,” which Nahr and Bilal read together while in a strict lockdown enforced by the Israeli military. Outside, there is chaos and truly dire conditions for the local population, but inside, the two are in this sort of love bubble, which makes for a very poignant parallel to the quote. Through the characters, you also draw attention to the larger resonance between the Palestinian struggle and other movements. Other scholars and activists, including Angela Davis, have also written and spoken about this connection. How does studying Palestine help us better understand the Black liberation struggle in the U.S., for example, and vice versa?

SA: I think internationalism is a pillar of true resistance. Building bonds and bridges with those who are fighting similar struggles and showing up for them is about moral consistency. We cannot call for an end to Zionism and at the same time look away from the oppression and marginalization of others.

My resistance is also feminist in nature. It is a vegan lifestyle in opposition to industrialized animal cruelty. It is militant and does not under any circumstance accept Zionism as anything but a modern face of white supremacy, however multi-racial that face might be.

susan abulhawa is a novelist, poet, essayist, scientist, mother, and activist. Her debut novel Mornings in Jenin (Bloomsbury, 2010), translated into 30 languages, is considered a classic in Anglophile Palestinian literature. Its reach and sales has made abulhawa the most widely read Palestinian author. Her second novel, The Blue Between Sky and Water (Bloomsbury, 2015), was likewise an international bestseller. Against the Loveless World (Simon & Schuster, 2020) was out in August. She is also the author of a poetry collection, My Voice Sought The Wind (Just World Books, 2013), contributor to several anthologies, political commentator, and frequent speaker. Abulhawa is the founder of Playgrounds for Palestine, a children’s organization dedicated to uplifting Palestinian children. She is also co-chair of Palestine Writes, the first North American Palestinian literature festival.

Rachael Rosenberg served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Georgia, where she developed the English education program at a school near the Georgian-Armenian border and led USAID-funded projects focusing on youth leadership, social activism, and gender equity. In 2017 Rachael spent a summer as a cultural ambassador for the USA Pavilion at the World Expo in Astana (now Nur-Sultan), Kazakhstan. She previously worked on research initiatives at the Kennan Institute and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, and won a Critical Language Scholarship for intensive language study in Russia from the US Department of State. She is currently a student in the Master of Global Affairs program in the Keough School of Global Affairs.