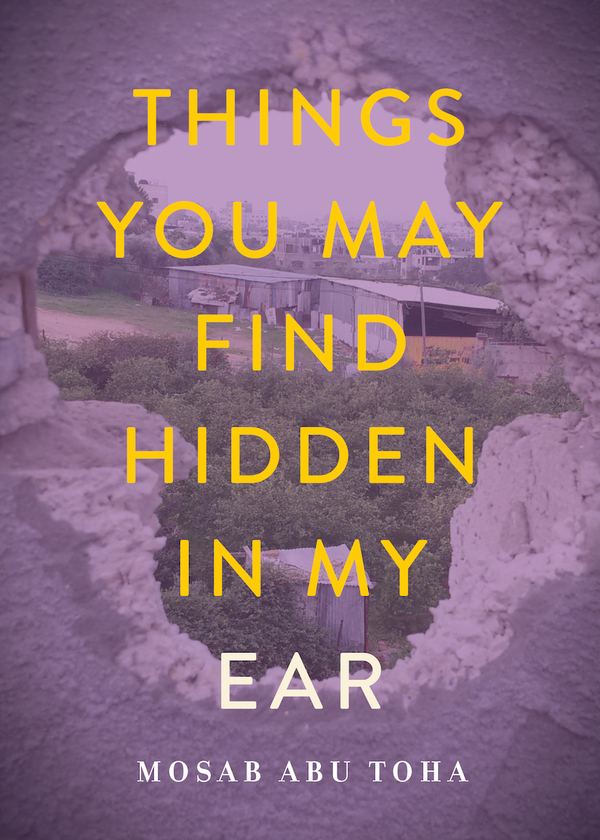

As Mosab Abu Toha writes in his poem, “Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear”:

“When you open my ear, touch it

gently.

My mother’s voice lingers somewhere inside.

Her voice is the echo that helps recover my equilibrium

when I feel dizzy during my attentiveness.

You may encounter songs in Arabic,

poems in English I recite to myself,

or a song I chant to the chirping birds in our backyard.”

Mosab Abu Toha was asked about the process of building a concept of “home” when physical space is under siege; how he views poetry and language(s)’s role in global society and as a means of connecting with others, crafting a deeper sense of “home”; and about his thoughts on current global society’s troubles in connecting with others, making it harder for knowledge sharing and creating a collective hominess amongst people worldwide.

Kristyn Garza: Seeing as how your poetry traverses boundaries of language and space and explores the conceptional confines of place, issues which one might consider highly political in nature, I can’t help but ask what you believe the role of language, more specifically the role of poetry is in global society? Do you think poetry is political by nature? There are many that would argue for the insistence that poetry should keep to its own microcosm of aestheticism but, then again, there are others who would argue the opposite—what are your thoughts on this?

Mosab Abu Toha: I think that writing, especially writing poetry, is not always a decision a poet makes. A poem can be a response to an experience or a reflection on it.

When I think of the word political, I don’t only imagine my position in the world in relation to others. It’s also about me as a human. As an individual. When I write, I talk to myself, I console myself, I complain to myself. Sometimes a poem is a reflection of me in the water of a raging sea. Sometimes it’s my image on a cloud that would rain on a barren field or a flattened neighborhood, or maybe on some green fields I can never reach.

On other occasions, I love to create and paint beautiful new images of a place that I never saw before, primarily because I cannot leave Gaza and visit other countries when/if I wish.

Anyone who’s unfortunate enough to be born in a country that never knew peace, particularly in the past 100 years, cannot but be involved (in writing at least) with occupation, siege, destruction, explosions, etc. But at the same time, there is the sea, sunrise, sunset, rain, flowers, birds, and animals. Therefore, if political is all about engaging with life in all its components, then poetry can never but be political.

KG: What are your thoughts on what constitutes home, place, or a space in which one belongs? Can home ever be forgotten? Can the conception and creation of “home” in relation to place be crafted using language that collects a variety of experiential details to create a sense of permanent identity as in your poem “Things You May Find Hidden In My Ear”? What are your thoughts on what language(s) should/can be used to create this metaphysical “home?”

MAT: A home can be your memory of your home garden, of the hen coop, of the road to school, or of the shade of a tree on your street corner. A home is your family and your tiny footsteps that you can still gaze at, that the wind could never wipe.

It’s everything you take with you when you travel—in your mind.

You store it in your ears, in your eyes, in your nostrils, in your tongue. It’s just that you need the right place to feel and build it when you are far from it. As if it wants a special device. Maybe a phonograph?

It’s not easy to find a home and call it one. It may take a life.

It’s more difficult for us in Gaza to form the notion of home. Usually, one feels what it means to be home when they travel and stay away from it for some time. One feels homesick. I felt it several times when I was in the United States two years ago.

Because of occupation, we sometimes have a vague notion of home. I wrote a poem titled, “Like a Cloud, We Travel”:

Wiped out by every wind over Gaza,

we are scattered on this earth,

footsteps in the desert.

We do not, or cannot, know

when and how to return

to the homes

our ancestors loved

for centuries.

Like clouds,

we try to give shade and rain:

the best we can.

But deep down, we do not know

whether we even belong

to where we happen to exist.

Like clouds,

we might visit our homes

without knowing that they still are

ours.

Invaders have changed much

of our landscape,

much or our lives.

KG: What is your take on English as a “global language”? There are some who view English as an oppressive force that silences other languages due to the long history of colonization and forced English acquisition. You mentioned in an interview with Philip Metres how you feel a sense of freedom writing in English, “free from the confinements of [your] existence in Gaza.” Would you say that a sharing of language, a borrowing from a “global/universal” language, helps in crafting a sense of home and global collective belonging and identity?

MAT:I don’t think that one cares or asks who invented electricity when they use it. The same goes for medicine and airplanes, etc. English, just as all languages, is a means of communication. It’s the most-spoken language in the world. When I speak and write English, my words travel farther than they do when I do in Arabic. Arabic is a beautiful language and I write in it, too. However, there are many things that the whole world needs to hear about which are put best in English. This language is the language of science and technology. It’s also the language of colonization and mass-destruction weapons. The language Balfour used to promise Palestine to the Jews of the world. The language that made my grandfather and his family dejected refugees. The language that deprived my grandmother of picking her oranges in Yaffa.

In a poem I wrote titled “In the Wreck of my Library,” I wrote:

Explosion!!!

Both the fly and I fall,

me on a mattress,

the fly, oh the fly,

a heavy Britannica Encyclopedia volume

smashes it.

A bookmark in that volume sticks out.

I open the marked page.

Balfour Declaration.

I tell myself,

“That volume, if it had only the 67 words

of that declaration in its pages, not only

the fly, but a whole country,

would be flattened.”

KG: Knowing that Gaza and its citizens are subject to state-sanctioned violence, lack of mobility, and oppressive economic restrictions, what do you think poetry’s role is in forging community resilience and in healing psychological wounds? I’m thinking specifically of your poem “my grandfather and home” and the lines “he forgot the numbers the people/he forgot home” and “for this home i shall not draw boundaries/no punctuation marks.” I’m interested in the tension these lines express between healing and forgetting in the face of mass trauma.

MAT: Poetry cannot change the details of people’s real lives. It cannot put food on the tables of poor families. It cannot bring back killed children from the dead. It can, however, affect how people perceive things around them if they choose to listen or read, especially those who live outside of the poet’s circle. As a Palestinian who lives in Gaza, I’m talking about people in the West, for whom it’s very hard to imagine having to live under occupation and siege for decades.

Most people worldwide began to feel what it means to be unable to travel and visit loved ones during Covid-19, what it means to keep social distancing and be unable to hug and kiss.

In Gaza, and also in the West Bank, people don’t have an airport at all. Not even a seaport. In the West Bank, people have to skip endless checkpoints to reach a neighboring village and visit a sick relative or bid farewell to a travelling cousin. A mother gives birth and may lose her life or the child’s at an Israeli checkpoint, when a pregnant mother has to wait for hours for an Israel permit to cross to a hospital.

Moreover, poetry can bring and spread memories of the sweet past of one’s family or nation. I live as a stateless person in my country. I cannot leave when I wish. If I leave, I cannot return when I wish.

But when I write and read, I can return not only to Gaza when I’m outside it, but also to Yaffa, my original hometown from which the Zionists expelled my grandfather and his family.

Because I cannot bring my grandfather to his home in Yaffa, I promised to build him one with my words. My English vocabulary will be the bricks that will build it. So English here is no longer a colonizing language but a liberating one.

KG: What would you say is the importance of the internet in crafting connection and facilitating self-empowerment? In an interview with Philip Metres you mentioned practicing English with Facebook friends in Gaza when the internet was available. What are your thoughts on the violence that has become much more apparent in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic in which so many, largely low-economic and BIPOC communities internationally, have been faced with a lack of connection and severe economic disadvantage due to their monetary inability to obtain access to the internet in an age in which the internet is not a luxury but a necessity?

I think it’s a bliss to be able to speak, in the first place.

MAT: I think it’s a bliss to be able to speak, in the first place. Many people cannot talk because of the social and political circumstances they are confined by. Having access to the internet is not a guarantee that people would speak what they should or want.

Talking about internet in Gaza, people are confronted by several troubles here, the first of which is the daily electricity outages. We get access to electricity for only 8 hours these days. Sometimes we get it for 2 hours in winter.

The second issue is the slow internet connection. The 2G, the network in operation in Gaza, allows calls and limited data transmission.

The third issue is that many people, due to the merciless economic situation, do not own a device of their own, such as a smartphone or a computer, to use the internet. They would visit cafes or use their neighbors’ or relatives’ devices.

Many times, internet would be used by the young people of Gaza to break their constant isolation due to the siege imposed since 2007. Many of them never left Gaza to watch, from behind their small screens, the world as it moves on. This makes internet access very necessary. To enjoy something one cannot even touch in reality is sometimes liberating, too.

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian bilingual poet, essayist, and short story writer from Gaza. A graduate in English language, he taught English at the UNRWA schools in Gaza 2016-2019, and is the founder of the Edward Said Public Library, Gaza’s first English language library (now two branches). In 2019-2020, Mosab became a visiting poet at Harvard University, hosted by the Department of Comparative Literature. He is also a columnist for Arrowsmith Press. Mosab’s poetry, essays, and short stories have been or will be published by Poetry, Solstice, Banipal, Periphery, Harvard Human Rights Review, Kikah, Middle East Eye. In 2020, Mosab gave talks and poetry readings at the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, the University of Arizona, and the American Library Association Midwinter Exhibits and Meetings. His first book of poetry, Things You May Find Hidden In My Ear, will be published in April 2022 with City Lights Books.

Kristyn Garza grew up in McAllen, Texas near the U.S./Mexico border. She moved from McAllen to Austin to pursue her degree in English Literature at St. Edward’s University where she earned her bachelor’s. Her poetry has been published in Apricity Magazine, The Sorin Oak Review, and New Literati. During her time as an undergrad, she served as the Editor-in-Chief of The Sorin Oak Review for the publication of its 30th Volume. She later held the position of President and Editor-in-Chief of New Literati for two years until her graduation. The twenty-two year old bisexual Chicana writes a lot about her experiences, identity, and culture as a borderland native; her struggles with mental illness and trauma; and most of her work is particularly interested in: violence, connection, borders/barriers/boundaries, and healing from physical, emotional, and mental wounds both as individuals as well as a collective. She is a student in the MFA program in Creative Writing at the University of Notre Dame.