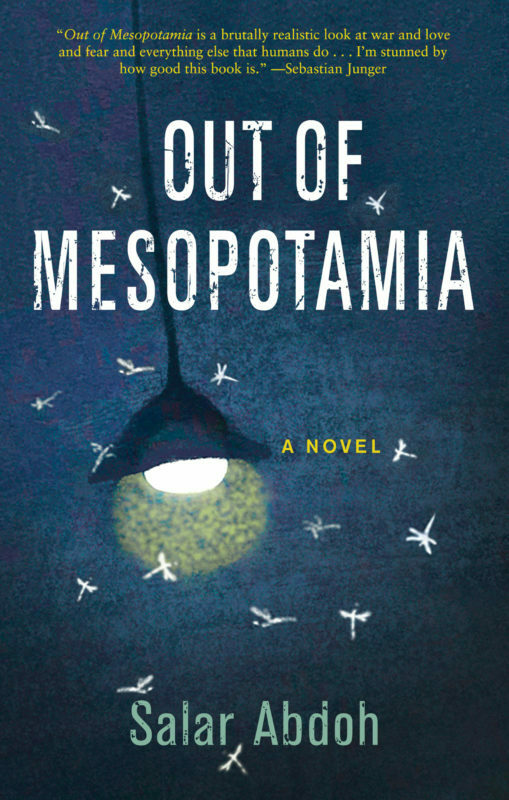

Salar Abdoh's Out of Mesopotamia follows Saleh, an Iranian journalist who moves between the art and entertainment world of Tehran and the battlefront of the war against the Islamic State. Saleh is caught in the middle—unable to truly take root in either world, and beset on all sides by a handler obsessed with Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, a Frenchman intent on dying in the warfront to escape his failed family life, a foreign scholar lurking in his emails, and various actors in the art and entertainment world hoping to use Saleh’s writing to various ends. I asked Salar some questions about the conception and execution of the novel.

Austyn Wohlers: Saleh’s magnetic attraction to would-be martyrs in Out of Mesopotamiawas very interesting to me—I think of Cleric J telling him “You are not the kind of man who takes the call. You only want to be near the men who do.” Could you speak to that? What interests Saleh about the suicidal?

Salar Abdoh: I wouldn’t call it “the suicidal.” Men, and women, who take the call in a time of war and/or occasions of severe resolution, do so for a variety of reasons, but it always goes back to having extreme conviction in something. That conviction is not necessarily always religious. But being around it, for a man like Saleh (or myself), is intensely attractive. To be in the proximity of the ultimate sacrifice, to experience it, and to know that beyond the dullness of one’s everyday a world and characters also exist who are impossibly romantic and potentially brutal and think nothing of dying can be exhilarating and damning. A man like Saleh is attracted to that. The adrenaline of battle is replaced by nothing and no one. It’s puerile, yes; but there it is.

AW: On the same note, some of the most gorgeous descriptions in the book were of the almost psychedelic rainbow glowing halos that surrounded those who felt an allure towards martyrdom. Where did this image come from? Is it something you’ve felt personally, or something you added to the novel towards some artistic end? I also think of the line “[A]ll the martyrs you’d known became one bandwidth of death, a rainbow of body parts and browned blood.”—There’s a real association of death with color in Out of Mesopotamia.

To be in the proximity of the ultimate sacrifice, to experience it, and to know that, beyond the dullness of one’s everyday, a world and characters also exist who are impossibly romantic and potentially brutal and think nothing of dying can be exhilarating and damning.

SA: The culture of death in Shia Islam is acute and all-encompassing. The rituals that derive from it are, to me, gorgeous and fierce. I am attracted to this world and its pageantry. The notion of the halo, in the way I speak of it in the book, first came about in the Iran-Iraq war. You can read account after account of warriors back then noting how those about to be martyred seemed to have a halo about them. I may not have seen a halo necessarily years later in another war in the Middle East, but I certainly saw that beatification and radiance. Not always, but often enough one really does sense when a brother is about to leave this world; they are ready.

AW: The novel straddles the worlds of both art and war, but I was especially interested in the ways these worlds seemed to cross-pollinate, especially in Saleh’s perception. Art infects Saleh’s interrogator H, who is extremely taken by Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past or In Search of Lost Time and continuously quotes the book to Saleh. On the other hand, Saleh sneers at the likes of Proust (the character, aka Daliri), whom he reads quite hostilely as an artistic failure (a “poor bookish fuck”) who is waiting for death. These reads seem integral to Saleh’s character—he feels warmly towards the government man who slowly develops an interest in art, but rather hostile towards a man who has pined for an artistic career since his university days. These interpretations of people seem integral to Saleh’s character to me—his conflicting attitudes towards figures of art and figures of war. Could you talk a bit about that?

SA: Saleh is not so much hostile to Daliri/Proust, but rather sees much of himself in the younger man. Saleh knows that the world of art and literature are by now (and maybe they always were) brimming with lies. Saleh is a man who writes for television, does art reviews, teaches literature at the university and also goes to war and reports from there (not unlike myself). In each of these settings he sees, correctly, an abundance of untruth and also sees himself as an integral part of this machinery of falsehood. Therefore, he despises himself, at least a little bit, and by extension, perhaps Daliri/Proust. But it is a distaste that is also mixed with love of all the things he does.

In Miss Homa, for instance, he finds truth in art. And in his martyred friends in Iraq and Syria he finds truth in war. Yet in both settings he also finds injustice, deceit and corruption of the soul.

In Miss Homa, for instance, he finds truth in art. And in his martyred friends in Iraq and Syria he finds truth in war. Yet in both settings he also finds injustice, deceit and corruption of the soul. He would like to save Daliri if he can, though the latter’s naivete certainly rubs him wrong sometimes. As for H, the interrogator, it would be easy to despise a man with such a job. But life is more complicated than that. And I have seen enough H’s in the world who are in fact not the monsters they are made out to be. Nuances are what we strive for in fiction, I would like to think.

AW: Miss Homa was such a singular character in the novel. So many novels wear outwardly the signs of failure: Saleh is frustrated with his love life and his financial precarity, Abu Faranci has lost his family, Proust/Daliri has not achieved his literary dreams. Miss Homa ostensibly does get what she wants—she is finally receiving fame and money from her paintings—but is disgusted by the way her life has changed as a result. How did you conceive of Miss Homa as a character? Is she based on anyone specific, or is she more a crystallization of a particular phenomenon for you?

SA: She is both, a crystallization of a particular phenomenon and also a specific person, in fact two specific people. One already gone from this world, and one to whom this is happening now to a certain extent, as the world of high art is indeed something of a monstrosity. I guess nothing in Out of Mesopotamia came out of complete fantasy. Except that the reaction of Miss Homa is not typical; that part of it I made up. I needed someone good from that world. A rarity. I had to create not her but her reaction to fame.

AW: The way you wove the narrative of the “enemy scholar,” who wants Saleh to conduct research for her on Tehran’s Jewish quarter, into the novel was quite deft. Her email emerges very much on the periphery—so much so that it’s easy for the reader to forget about it—and eventually this peripherality is precisely what allows H to exchange emails with her from Saleh’s account. Like Saleh, the reader is blindsided by something they’ve almost forgotten about, allowing us, in a sense, to feel the same thing as him in that moment. Could you talk a little about that plotline? What compelled you to include it?

And, as you correctly note, it also allowed me to give more body and depth to the entire novel from a perspective of love, not war, or perhaps love or potential love in a time of war.

SA: I will be truthful; there is indeed an “enemy scholar.” Sometimes in life you want to simply pay tribute to someone. And especially to someone whom you have, well, loved, but ultimately could not be with because of various reasons, including circumstances of history and geography and hostility between your nations. A bit of a Westside Story – I know. I’m in Tehran now and that person is elsewhere and I think of her often. I wanted her in my story. The subplot was a tribute and vice-versa. And, as you correctly note, it also allowed me to give more body and depth to the entire novel from a perspective of love, not war, or perhaps love or potential love in a time of war.

AW: I was blown away by the dialogue in Out of Mesopotamia—even during exchanges with no dialogue tags at all, you could almost see the characters register what their interlocutor was saying, digest it, and formulate something to advance their own position. So much is implied in those line breaks. How do you approach writing dialogue? Is there a particular philosophy you apply to it? Do you write these scenes very carefully, or hammer them out over a couple of drafts?

You cannot really write about the conversations of would-be-martyrs unless you’ve been close to them, bunked with them, eaten with them, and maybe even seen one or two of them arrive at their desired end right in front of you.

SA: I admit that dialogue writing comes more easily to me than other aspects of the novel. I can be quite terrible at the description for example. But by nature, I am a dialogue writer and I think I honed the craft by writing strict genre novels in my first couple of books. I can hear these people speak, I see them and feel them. They are there in front of me as if I were watching a movie. Usually, the dialogues happen in one shot, and seldom do I have to go back and do much more to them. I do not have the same luck with doing description on the other hand. I guess we ride on the things we are better at and try to better the things we are not so good at. In my writing, it also helps to have had proximity with certain people and situations. You cannot really write about the conversations of would-be-martyrs unless you’ve been close to them, bunked with them, eaten with them, and maybe even seen one or two of them arrive at their desired end right in front of you.

Salar Abdoh is an Iranian writer whose novels include Tehran at Twilight, The Poet Game, Opium, and, his latest, Out of Mesopotamia. He also is the editor of Tehran Noir, and has published essays on war and politics in journals such as Guernica and Words Without Borders. He currently splits his time between Tehran and New York City, where he teaches in the M.F.A. program at the City College of New York.

Austyn Wohlers is a writer from Atlanta, Georgia. Her work has appeared in Asymptote, Short Fiction, Yalobusha Review, and elsewhere. She is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Notre Dame.