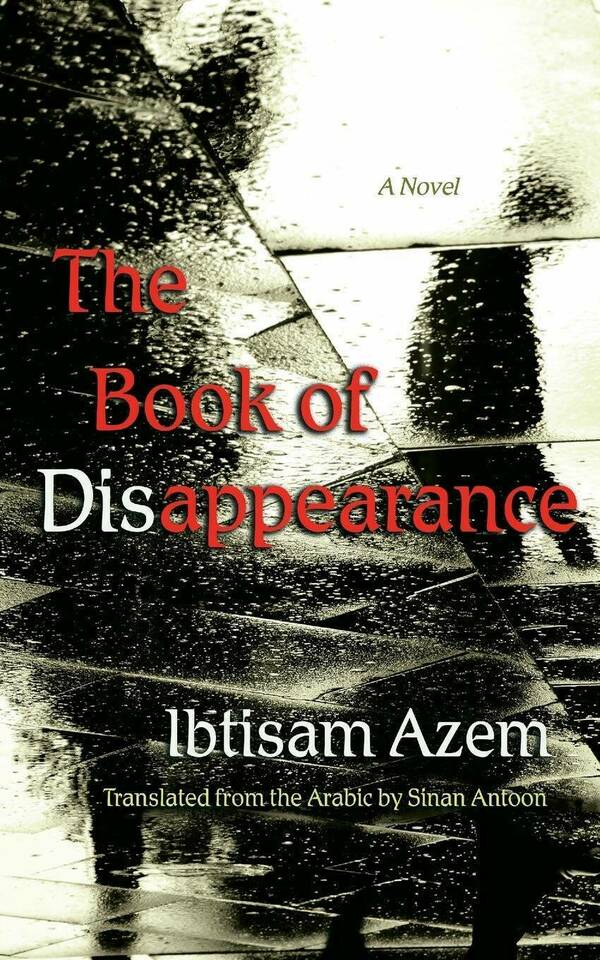

Ibtisam Azem is a Palestinian journalist and novelist from the northern Jaffa town of Taybeh. She studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and received an MA from Frieburg University in Germany. She is currently a senior correspondent for the Arabic Daily al-Araby al-Jadeed and the author of Sifr al-Ikhtifaa, translated into English as The Book of Disappearance. In this poetic and mysterious novel set in the city of Jaffa, Azem explores the aftermath of the sudden disappearance of all Palestinians from the land of historic Palestine. Azem touches on themes of erasure, loneliness, memory, and loss as she weaves together the stories of Alaa and Ariel to illuminate the unsettling reality of the Zionist project.

As Azem writes in her novel:

“Your Jaffa resembles mine. But it is not the same. Two cities impersonating each other. You carved your names in my city, so I feel like I am a returnee from history. Always tired, roaming my own life like a ghost. Yes, I am a ghost who lives in your city. You, too, are a ghost, living in my city. And we call both cities Jaffa.”“I memorized their stories and their white dreams about this place [Jaffa] so as to pass exams. But I carved my stories, yours, and those of others who are like us, inside me. We inherit memory the way we inherit the color of our eyes and skin. We inherit the sound of laughter just as we inherit the sound of tears. You memory pains me.”

Mathilda Nassar: There are many themes beautifully threaded throughout The Book of Disappearance. To me, the most prominent theme is that of loneliness. This loneliness assumes of loss. How has the nature of this loneliness impacted your sense of identity, as a Palestinian?

Ibtisam Azem: This is a difficult question because it takes me back to a constellation of emotions and the initial realization of this loneliness. It assumes different meanings depending on time, place, and the space through which we move and our relationships to others. Personally, I don’t think the identities one carries within can be completely separated. At certain stages or situations one of these identities or aspects of identity is foregrounded more than others. There are various factors that influence and inflect one’s identity such as gender, class, nationality. There are moments when loneliness is compounded for me as a woman confronting patriarchy in her native society. But when confronted with the micro aggressions and sexism of Israeli society, it is triply traumatic because it is then directed at me as a Palestinian woman. Loneliness takes different forms, but there is one thread that connects them and it is of being a Palestinian and trying to tell your story to the world as you see it. It is akin to speaking to a group of people who are hard of hearing and turn their back to you. I feel less lonely when I am in the company of, or in conversation with, those who lived under oppressive systems or in settler colonial societies, because they try to listen genuinely to understand us. Listening is the key word here.

What I have learned is to move my internal compass and that ethical criteria and justice must be the bases. It might sound odd if I say that I no longer hate that feeling of loneliness. I try to turn this loneliness to a space for contemplation. But one must also be careful so that one doesn’t shut out the world. It is also important for me to connect with others and their struggles and to be in solidarity with them.

In the last scene of the novel, Alaa describes something similar in terms of his attempt to transform loneliness and to even celebrate it. In spite of being colonized, he tries to decolonize himself and reestablish his relationship to his space and homeland. To learn to love it and to exorcise the colonizer’s memory from his mind. It is a difficult process of course.

I feel less lonely when I am in the company of, or in conversation with, those who lived under oppressive systems or in settler colonial societies, because they try to listen genuinely to understand us. Listening is the key word here.

MN: In the novel, Alaa’ wrestles with his grandmother’s memory of Palestine and the Palestine he knows (or doesn’t know). As a West Bank Palestinian, myself, I struggle to grasp what my Palestine is. What is your Palestine?

IA: Home. And intense belonging to its entire topography: the coast, the mountains, and its desert, as well as its dialects, tales, music, food, arts, and the people and their resistance. That stubbornness and clinging to life and the faith in one’s rights and the desire to be free. Irrespective of maps and names that try to erase its name, it remains my homeland and I feel I’m an extension of it. But it is also more than a “piece of land.” It is an idea and a cause that lives and extends to its vast diaspora with every refugee. Palestine is also a vision for a future of justice and equality. A way of being in the world.

MN: Generally, the world coerces and reinforces Palestinian silence. My grandmother was born in Jaffa, but she came to Bethlehem during the Nakba. Her story is as elusive as Alaa’s grandmother’s story. How can we as Palestinians ensure that our stories don’t die when we do?

After more than a century of colonization and more than seventy years of the Nakba, the cause is still alive. We are still narrating our history and resisting. We are working so that those stories are not forgotten and the proof is that we are discussing them here.

IA: After more than a century of colonization and more than seventy years of the Nakba, the cause is still alive. We are still narrating our history and resisting. We are working so that those stories are not forgotten and the proof is that we are discussing them here. Preserving our narratives, whether by archiving them or through other forms and genres is important, but what is more important is disseminating them widely and opening up to the narratives of other colonized peoples and learning from them and cooperating with them. It is important not to think of ourselves as eternal victims, but humans who are vulnerable and who make mistakes, but are resilient and continue to resist.

MN: After the disappearance, the dialogue between Ariel and Alaa’s notebook keeps the story going. What did you hope to convey through this exchange?

IA: I am not sure I would call it an exchange. In the red notebook the Palestinian speaks for the first time without waiting for anyone to listen or comment. He is writing his diary or memoir and it is the type of writing in which the writer is preconditioned to delving deep into themselves and contemplating their subjectivity and, hopefully, attaining a more expansive perspective. Through the practice of writing, the Palestinian takes charge of his own narrative. He tells his own story and, theoretically, no one can silence him or stop him. This is why Alaa’s chapters are his alone and are separate from Ariel’s who can only comment in his own chapters. Thus, for the first time, Ariel listens without being able to force Alaa to hear his response.

MN: The story about the girl in Dayan’s memory is told through the eyes of the perpetrator. Who is the girl and why is Dayan given ownership of this narrative?

IA: I disagree. He is not the one telling the story. It is the omniscient narrator. It is true that we don’t hear her voice. We are in his world and that’s intentional. The story here is not just about the rape. What I tried to do here is inspired by Handala, the iconic character created by Naji al-Ali. Handala was the Palestinian refugee child who appears to be turning his back to the world, but the reality is that it is the world which had turned its back to Handala and sees him as such. The story in the novel is influenced by the idea behind Handala, but I took it somewhere else. The woman in the story has been sitting outside her house in Jaffa since the Nakba and telling her stories, but no one listens to her, including her family, meaning her Palestinian society. Nor do the Israelis listen, of course. They all think of her as being insane. Like Handala, no one tried to listen to her, talk to her, or to understand what she is saying. Dayan, the perpetrator, stayed silent all these years. Like these colonizers who lived through the Nakba and at times they speak of acts they committed, or saw, and remain silent. Just as those who are silent today in regards to what befalls Palestinians. The story is about the silence that continues. Even after the woman disappears, Dayan stays silent. The silence is, in a way, a continuation of the violent act the silence is covering or denying or ignoring. What does Dayan do after the woman disappears? He blames her. The story is a mirror of sorts for the perpetrators, their silent accomplices, and the silent bystanders.

MN: The novel implies (and possibly reveals) that the only way to fully realize the Zionist dream is through the complete erasure of Palestinians. How do you think a critic might respond to this allegation?

IA: I beg to differ. The novel does revolve around the total disappearance of Palestinians, but it takes this event beyond the colonial ideology of Zionism which wants to erase and replace the colonized. It is primarily concerned with Palestinians and what their disappearance means. There is the actual “disappearance” that took place in 1948 and resulted in the expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their land and denying them the right of return. But this right is still valid and recognized by international bodies and laws, notwithstanding all the limitations and problems with the UN and its resolutions.

There is another aspect to the disappearance which is the sense of liberty the Palestinian feels as if saying, through this disappearance, that the game is over as far as s/he/they are concerned. And, as a reminder, the reasons for the disappearance are never clear in the novel.

The novel confronts the colonizer with a mirror, but, more importantly, it explores with dark sarcasm, the colonizer’s practices. It poses the question: what will states/ nations that base their identity on the “enemy” do once that “enemy” disappears?

There is another symbolism in disappearance, that the Palestinian is “invisible” unless and except when s/he/ they are a “problem.” The novel poses many questions and contemplates reality from the perspective of Palestinian characters who remain the axis despite their eventual silence represented by their disappearance.

This interview was conducted via email following the Literatures of Annihilation, Exile and Resistance event from October 2, 2020. You can watch the recording of the event with Ibtisam Azem, featuring the discussant, Hilary Rantisi, Associate Director of the Religion, Conflict and Peace Initiative and Senior Fellow at the Religious Literacy Project at Harvard Divinity School, and moderator by Nazli Koca, Notre Dame MFA alum. This event was co-sponsored by the Religion, Conflict, and Peace Initiative at Harvard University.

Ibtisam Azem is a Palestinian short story writer, novelist, and journalist, based in New York. She studied at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and later at Freiburg University, Germany, and earned an MA in Islamic Studies, with minors in German and English Literature. In 2011 she moved to New York where she lives now and works as a senior correspondent covering the United Nations for the Arabic daily al-Araby al-Jadeed. She is also co-editor at Jadaliyya e-zine.

The Book of Disappearance is her second novel in Arabic. It was translated by Sinan Antoon and published by Syracuse University Press in July 2019. Some of her writings have been translated and published in French, German, English and Hebrew and have appeared in several anthologies and journals. She is working on her third novel and she just finished another MA in Social Work from NYU’s Silver school.

Mathilda Nassar is pursuing a Master of Global Affairs in International Peace Studies at Notre Dame’s Keough School of Global Affairs. Her research focuses on the intersection of somatics, identity, and decoloniality. She is particularly interested in exploring embodied knowledge and its role in understanding displacement, especially in terms of coloniality. She draws on her experience as a native Palestinian, her passion for dance, her academic studies, and her professional work in peacebuilding capacities to inform her research as well as her sense of what it means to “be” in the world.