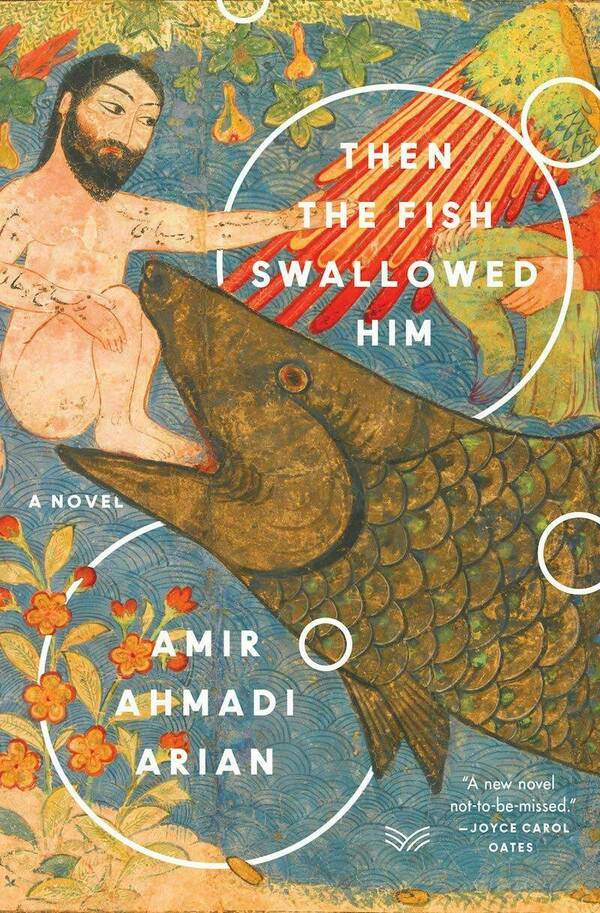

Then The Fish Swallowed Him, Amir Ahmadi Arian's first novel in English, follows bus driver Yunus Turabi as he participates in the mid-2000’s Tehran bus drivers’ strike, is arrested, and is sent to Evin Prison, a facility notorious for housing Iran’s political prisoners. From there, a bleak, absurd, and psychologically harrowing narrative of isolation and torment emerges as Yunus endures long periods of solitary confinement and manipulative questioning by his interrogator, Hajj Saeed. I asked Amir about his research process, characterization in prison narratives, class tensions in the structure of the novel, his switch to writing in English, and the task—for Arian and Yunus both—of finding the beautiful in the profane.

Austyn Wohlers: In Then the Fish Swallowed Him’s Acknowledgements, you talk about chatting with numerous Iranians who spent time in solitary confinement, as well as bus drivers. What sorts of details from these conversations ended up bearing on Yunus’s story? You speak elsewhere of the fact that your work as a journalist and your work as a fiction writer has been simultaneous, rather than sequential, so I’m also interested in hearing about how those two sides of yourself might have played off one another during your research and writing, or if you had to struggle to separate them. Did your journalistic training help with the economy of storytelling, for instance? Did you find it easy to convert your notes into plot and description?

Amir Ahmadi Arian: As a writer, you learn that there are things you can’t just think up and put to words. Certain human experiences defy language, and the only way to approach them is to either experience them yourself or to conduct very deep and thorough research.

The death of a loved one is a good example. Without the first-hand experience, or at least inhabiting the mind of someone who has experienced it, you can’t really write about it.

Before starting to work on this novel I never thought of solitary confinement as a kind of human experience that language can’t capture. I read a few scholarly books and first-hand accounts, even tried to simulate the conditions of solitary confinement, but none of that worked. The next best thing I could do was talking to people who had that experience.

If you lived in Iran and were involved in politics, unfortunately you will probably have multiple friends who qualify. So I called about half a dozen people, and interviewed them about their time in solitary confinement. It was a difficult, sometimes frustrating process, because many of them were unwilling to talk about it. The trauma was deep. The wound still hurt. Understandably they didn’t appreciate me trying to poke at it. But I eventually managed to gather enough material to get me through those chapters.

This is my roundabout way of saying that without those interviews this novel wouldn’t have existed.

As for my past in journalism, maybe I shouldn’t have brought it up, because there is nothing special about it. Journalism is what pretty much all Iranian authors, at least in my generation, had to do. The lines that separate different forms of writing are rather blurred in Iran. As a writer, it is very common that you publish poetry, short stories, journalism, personal essays, newspaper columns, and novels. In fact, if you say I only write fiction because I am a novelist, that sounds sort of obnoxious. Since I came up in that culture, I never thought about how these two sides of me would interact. This is a question I get in the US all the time, but since it has never been a concern of mine I don’t have a good answer for it.

AW: The structure of the book was very compelling to me: you start and end on violent, chaotic scenes of strike/protest which bookend the long, lonely, claustrophobic middle, which comprises Yunus’s time in prison. The former, the working-class bus drivers’ strike, is reviled by many of the other characters as a destructive gridlocking of Iranian infrastructure, while the latter, a youth-led protest which also interferes with infrastructure by blocking off the highway, is applauded by nearly everyone Yunus speaks to. There’s also the interesting scene where a college student approaches Yunus happy that “the working class has come out to support the strike,” then tries to get a picture with them. Could you talk a bit about these scenes, politically and structurally? Was there a class comment intended there, or maybe a comment on how attitudes have shifted during Yunus’s time in prison?

AAA: It is very much a class comment, and I am glad you picked up on it because no one I have spoken to brought this up. The events that bookend this story are similar in that both are popular uprisings against the powers that be. Yet they are quite different from each other. The first one is a union strike, organized by workers, with a small number participants. It has a specific purpose. Every step of the way is pre-designed and thought-through.

The last scene is a mass uprising, a sudden explosion of rage which brought three million people to the streets of Tehran in 2009.

The last scene is a mass uprising, a sudden explosion of rage which brought three million people the streets of Tehran in 2009. It didn’t have a particular agenda or a clear goal. The former was organized and carried out specifically by the working class, the latter was open to everyone, though the crowd mainly consisted of university students, the middle class, secular-leaning residents of the more affluent neighborhoods of Tehran. There is a class tension there, which I tried to convey in the interaction between Yunus and the student protester at the end of the book.

AW: Early in the novel, Yunus resolves to search for beauty despite the miserable conditions of solitary: “Finding the beauty in the beautiful was redundant, I told myself. Finding it in the dull, the abject, was the task ahead.” From that resolution derives many of my favorite passages in the novel, with Yunus finding company in the fly who feeds off his vomit, comfort in the pigeon shit in the jailyard, et cetera. Could you speak a bit about that theme? Do you think it bears on the novel in a larger way than in Yunus’s attempts to psychologically make it through his confinement, or perhaps on your thoughts about fiction in general?

As a form, the novel has a unique capacity to contain all sorts of details. It gives you room to zoom in and out, to look at every small thing from a variety of angles, to deploy the power of language in order to impart importance to the seemingly insignificant.

AAA: Famously, in one of his lectures Nabokov advised his students to “notice and fondle the details.” I think it is an excellent advice. A structuralist cliché holds that there are only so many stories, only so many character types you can create. But the realm of details is infinitely open. As a form, the novel has a unique capacity to contain all sorts of details. It gives you room to zoom in and out, to look at every small thing from a variety of angles, to deploy the power of language in order to impart importance to the seemingly insignificant.

I think it is no exaggeration to say that what distinguishes a great novel from a mediocre one is not so much the characterization or plotting as the way the author writes about the details. So there was a craft element involved.

Before embarking on my research interviews, I was aware that the little details we barely notice when we are free take on a huge significance in the solitary, but I failed to appreciate the extent of this change, until I talked to the people who have been there.

AW: In other interviews, you’ve mentioned switching to English largely due to the censorship of your books in Iran. Could you speak about that? Conversely, how did writing this book for an Anglophone audience impact your writing? Do you think it led to any stylistic or narrative concessions?

AAA: I have published about ten books in Persian, authored and translated. I learned English early in my life and have been reading things in English my whole life, but I never regarded it as my writing language. Even after The Ministry of Culture banned two of my books I still didn’t consider switching to English.

The very possibility of living as a writer in Iran was essentially eliminated for me.

Things changed in 2009. I was closely involved in the political uprising that came to be known as the Green Movement. It got brutally crushed. The life and well-being of those of us involved came under serious threat. The newspaper I worked for was shut down. The publisher I was editing for was shut down. A lot of my friends were arrested and taken to the very prison where the events of this book take place. Every night I went to sleep expecting a knock on the door and the raiding of my apartment. So it wasn’t just censorship, or even safety.

I applied for PhD positions outside Iran because that was my only way of getting out other than becoming a refugee, and prioritized Australia because my partner at the time was Iranian-Australian. In my second year in Australia, in 2012, I decided to write the rest of my books in English. I was already past 30 at the time, and had never seriously considered writing fiction in English. Switching language at that age for a novelist is a huge risk if not flat-out madness, and I had very little hope that it would pay off.

Writing for the Anglophone audience wasn’t as challenging as I expected. I didn’t really make any concessions, stylistically or thematically, at least not consciously. There are parts in the book where I had to add a bit of context or include information that an Iranian audience would find redundant, but those are only a few passages. If I were to write this book in Persian maybe it would be a couple of pages shorter. That’s about it.

AW: This book reminded me of many other great novels about intense relationships between two people in a setting of captivity—I think of Valentin and Luis in Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman, or Hoja and the narrator in Pamuk’s The White Castle. Yunus and Hajj Saeed’s relationship is complex; both seem to feel empathy for the other at certain points, and their attitudes towards one another is constantly shifting between what feels like personal attachment or hatred and the imposition of some other force. For Hajj Saeed, of course, this force is the State. What was the development of these two characters and their relationship like? Is there any hope for Hajj Saeed, in your opinion?

AAA: Both of the books you mention have influenced on me, especially Kiss of the Spider Woman. My book, among other things, a story of bureaucracy. Hajj Saeed and Yunus are operating within a system. I hope I was able to convey that none of Hajj Saeed’s moves are spontaneous. The cat-and-mouse, the occasional beating, the rapid shifts from the very personal to the very general during the interrogations, all of that are already in the books. He is a seasoned, professional interrogator, strictly following a protocol. I try to lay bare a system through the interactions of these two characters, to show how the beast that swallowed both of them is pitting them against each other.

I am not sure if the word “hope” applies here. There is no hope for the system, that much I can say. Many of the interrogators after the revolution used to work for SAVAK, the Shah’s police. They just got back to work after the revolution and applied the same technics to their subjects, except that their former bosses were now their prisoners. As long as the system is operating so effectively, individuals are interchangeable. The destruction of this machine should be the goal.

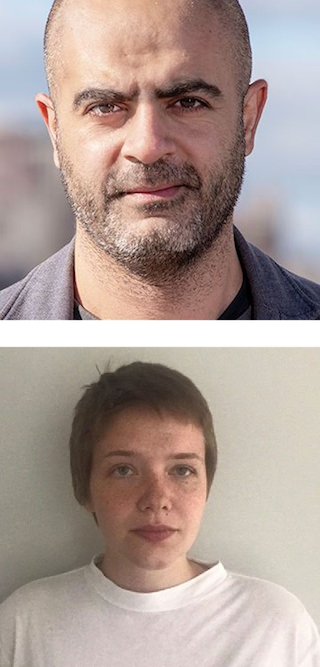

Amir Ahmadi Arian started his writing career as a journalist in Iran. He has published two novels, a collection of stories, and a book of nonfiction in Persian. He also translated from English to Persian novels by E.L. Doctorow, Paul Auster, P.D. James, and Cormac McCarthy. Since 2013, he has been writing and publishing exclusively in English. In recent years, his work has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, LRB, and Lithub. He holds a PhD in comparative literature from the University of Queensland, Australia, and an MFA in creative writing from NYU. He currently teaches literature and creative writing at City College, New York.

Austyn Wohlers is a writer from Atlanta, Georgia. Her work has appeared in Asymptote, Short Fiction, Yalobusha Review, and elsewhere. She is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Notre Dame.